I read a lot of Thomas Mann in school and really enjoyed most of it, though I will acknowledge that Doctor Faustus sailed right over my teenaged head. Does anyone now write like Mann or, say, Nabakov? Should they? Theirs was a denser type of literature that seems mostly absent now. Those complexities are found more in visual culture today. The opening of a 1955 interview Frederic Morton of the New York Times did with Mann just two months before the writer died:

Travemuende, Germany — Thomas Mann’s eightieth birthday–June 6–might suggest an aged Olympian gazing distantly upon the world from his Lake Zurich retreat. The picture, however, is not entirely accurate. Before meeting this writer, for example, the Nobel prize winner had just delivered speeches on Schiller in Stuttgart and Weimar, negotiated possible film sales of Buddenbrooks and The Magic Mountain in Goettingen and spoken on the North German radio. Soon after the interview he was to receive Honorary Citizenship of his native city (Luebeck), be the object of a number of official birthday fêtes in Zurich, launch a lecture tour in Holland and, last not least, complete his Felix Krull, which recently appeared (442 pages strong and briskly subtitled “First Volume of the Memoirs”) to a volley of German critical huzzahs.

Travemuende, the Baltic Sea resort in which this writer cornered the octogenarian, was supposed to provide a brief lull for the Herr Doktor. (In Germany, where every solvent person with spectacles is presumed to possess a Ph.D., Thomas Mann goes by the title of the Herr Doktor.) His hotel suite, though, could have been the opening-night dressing room of Mary Martin. Flowers, telephone calls, telegrams and she whom even Miss Martin could never boast of, namely Katja Mann. For to interview Herr Doktor means invariably also to interview Frau Doktor, his attractive and most vivacious wife, whose conversational impulses have a wonderful way of advancing, instead of interrupting, a causerie. On this visit she wore a smart (one is almost tempted to say snappy) turquoise velvet jacket with embroidered sleeves. During the talk she directed traffic between a messenger boy, a hotel official, the interviewer and a maid pouring tea.

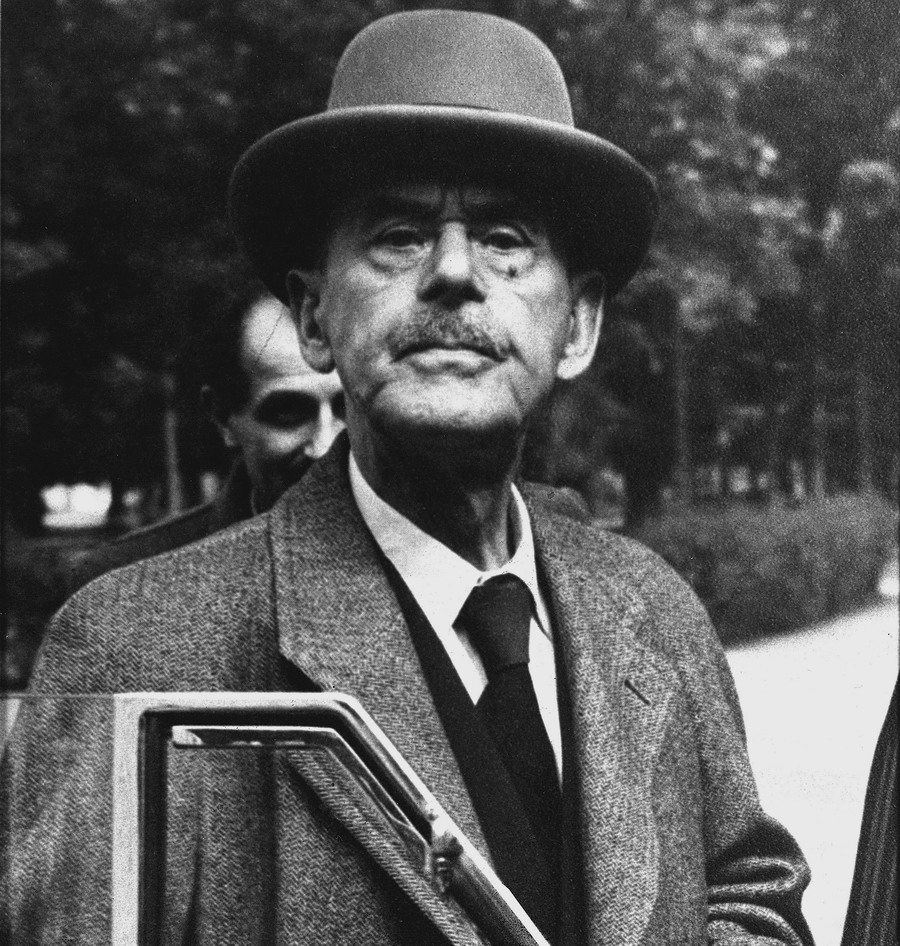

In the midst of it all, the master. Clad in business gray, hands factually folded, he looked about fifteen years younger than his age and much more (there’s no help for the word) bourgeois than even his photographs. In fact, he resembled a Hanseatic grain merchant pondering, in the solitude of his office, wheat futures on the Hamburg bourse. His actual problem, just put to him by the visitor, was a little different.

“I am not sure if I consider any one book my most important,” he said in his precise but measuredly cadenced High German. “The longest and, to my mind, richest work is the Joseph tetralogy, but perhaps–” the Mann smile like the Mann phrase often has a decorous ambiguity, regretful and self-ironical at the same time “–perhaps I like ‘Joseph’ best by way of overcompensation. Because of its size it is the last read of my major works, you know.” He turned to light a cigar. “Then of course there is the Faustus which put the heaviest strain on my resources and in that sense is closest to me. And there is ‘Tonio Kroeger’; it is the most private and emotionally most autobiographical thing that I have ever done.”•

Tags: Frederic Morton, Katja Mann, Thomas Mann