From “Kodak’s Problem Child,” Kenny Suleimanagich’s Medium article about how George Eastman’s marvelous company was laid low by its inability to capitalize on its own innovation:

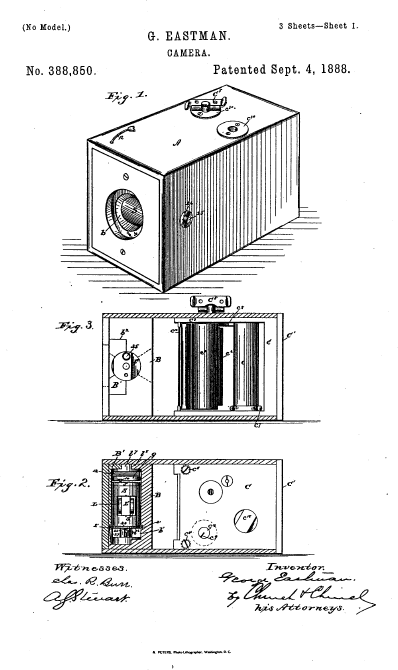

“Chemistry was work that Eastman himself, with one foot still planted in the nineteenth century, well understood. Over the span of about a decade, the Kodak founder invented the first practical roll film and then built the first cameras that could reliably use it. Never again would photography be a cumbersome process, the domain of professionals only.

In his original patent, he wrote that his improvements applied to ‘that class of photographic apparatus known as ‘detective cameras,’’ — concealed and disguised devices, made possible by a new wave of miniaturization, that were used mostly for a lowbrow entertainment: snapping pictures of people unaware. Cameras equipped with single-use chemical plates were hidden in opera glasses, umbrellas, and other everyday objects, and sharing the surreptitious, random, and sometimes compromising photos that resulted became a popular fad.

Eastman, in other words, was obsessively tinkering with what many people at the time would have considered a cheap novelty or a toy. Like Netflix in its early days, Kodak relied on the U.S. Postal Service: Customers sent their spent cameras to Rochester, where the film was removed, processed, and cut into frames; the resulting negatives and prints, along with the camera, reloaded with a fresh roll of film, were returned to the sender. Suddenly it was easy for anyone to take lots of pictures, and Eastman’s new business became a juggernaut almost overnight.

About ninety years later, another tinkerer in Kodak labs would create an integrated circuit that turned light waves into digital images. It too would be labeled a toy by the few people who saw it. It too would eventually launch a huge new business all but overnight. But this time, Kodak wouldn’t be part of it.”

Tags: Kenny Suleimanagich