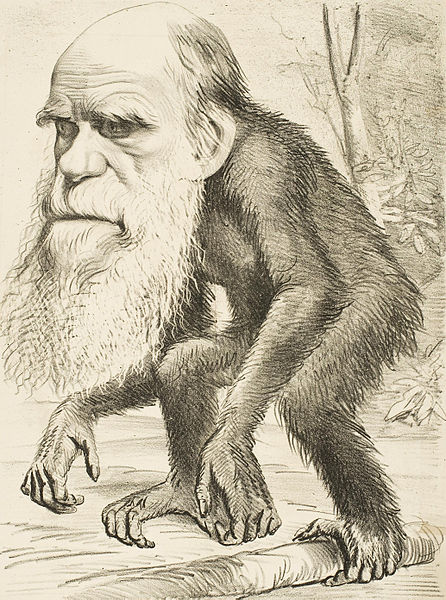

From “Dorothy, It’s Really Oz,” the late paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould’s 1999 essay about that stubborn foolishness Creationism, which has since morphed into the idiocy known as Intelligent Design:

“In the early 1920s, several states simply forbade the teaching of evolution outright, opening an epoch that inspired the infamous 1925 Scopes trial (leading to the conviction of a Tennessee high school teacher) and that ended only in 1968, when the Supreme Court declared such laws unconstitutional on First Amendment grounds. In a second round in the late 1970s, Arkansas and Louisiana required that if evolution be taught, equal time must be given to Genesis literalism, masquerading as oxymoronic ‘creation science.’ The Supreme Court likewise rejected those laws in 1987.

The Kansas decision represents creationism’s first—and surely temporary—success with a third strategy for subverting a constitutional imperative: that by simply deleting, but not formally banning, evolution, and by not demanding instruction in a biblically literalist ‘alternative,’ their narrowly partisan religious motivations might not derail their goals.

Given this protracted struggle, Americans of goodwill might be excused for supposing that some genuine scientific or philosophical dispute motivates this issue: Is evolution speculative and ill founded? Does evolution threaten our ethical values or our sense of life’s meaning? As a paleontologist by training, and with abiding respect for religious traditions, I would raise three points to alleviate these worries:

First, no other Western nation has endured any similar movement, with any political clout, against evolution—a subject taught as fundamental, and without dispute, in all other countries that share our major sociocultural traditions.

Second, evolution is as well documented as any phenomenon in science, as strongly as the earth’s revolution around the sun rather than vice versa. In this sense, we can call evolution a ‘fact.’ (Science does not deal in certainty, so ‘fact’ can only mean a proposition affirmed to such a high degree that it would be perverse to withhold one’s provisional assent.)

The major argument advanced by the school board—that large-scale evolution must be dubious because the process has not been directly observed—smacks of absurdity and only reveals ignorance about the nature of science. Good science integrates observation with inference. No process that unfolds over such long stretches of time (mostly, in this case, before humans appeared), or at an infinitude beneath our powers of direct visualization (subatomic particles, for example), can be seen directly. If justification required eyewitness testimony, we would have no sciences of deep time—no geology, no ancient human history either. (Should I believe Julius Caesar ever existed? The hard bony evidence for human evolution, as described in the preceding pages, surely exceeds our reliable documentation of Caesar’s life.)

Third, no factual discovery of science (statements about how nature ‘is’) can, in principle, lead us to ethical conclusions (how we ‘ought’ to behave) or to convictions about intrinsic meaning (the ‘purpose’ of our lives). These last two questions—and what more important inquiries could we make?—lie firmly in the domains of religion, philosophy and humanistic study. Science and religion should be equal, mutually respecting partners, each the master of its own domain, and with each domain vital to human life in a different way.”

••••••••••

Gould disccuses evolution in 2000 with that affable dinosaur Charlie Rose:

More Gould posts:

Tags: Stephen Jay Gould