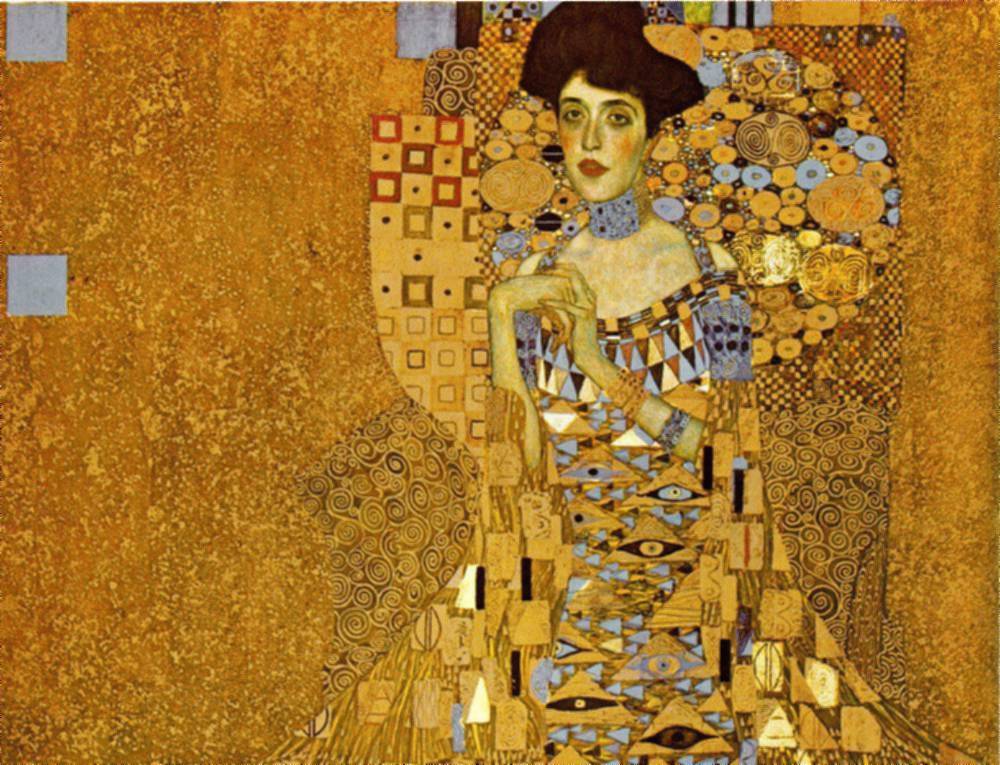

"Crowds lining up to see a portrait by Gustav Klimt in the private Neue Galerie in New York weren’t there out of any fondness for the artist."

Eye-popping prices for artworks are a puzzlement for people outside of that world–and for many people on the inside. In Newsweek, Blake Gopnik attempts to explain why this market is impervious even to worldwide financial collapse. An excerpt:

“‘If I can’t sell something, I just double the price.’ That’s what Ernst Beyeler, the great Swiss dealer who helped found Art Basel, reportedly said. Some people actually prefer to pay more than makes sense. Zelizer explains that, in all walks of life, we treat the biggest sums -differently, with special respect or even awe, than more-everyday money. ‘I think very often the price paid for a work is the trophy itself,’ says Glimcher, the dealer.

In 2006, the crowds lining up to see a portrait by Gustav Klimt in the private Neue Galerie in New York weren’t there out of any fondness for the artist. They were there because they’d heard that the museum’s founder, cosmetics heir Ronald Lauder, had paid a record $135 million for it.

The sociologist Mitch Abolafia, who has made a study of Wall Street financiers, says that sometimes money speaks for itself. ‘A trader said to me one day, with glee in his eyes, ‘You can’t see it, but money is everywhere in this room. Money is flying around—millions and millions of dollars.’ It was a generalized excitement about money. Even I felt it.’ That’s the excitement we all get from expensive art. One collector, who believes deeply that art should be bought for art’s sake, acknowledges basking in the ‘robust glow of prosperity’ that his purchases give off once their value has soared.

The people who are spending record amounts on art buy more than just that glow. (And much more than the pleasure of contemplating pictures, which they could get for $20 at any museum.) They’ve purchased boasting rights. ‘It’s, ‘You bought the $100 million Picasso?!,’’ says Glimcher. Abolafia explains that his financiers were ‘shameless’ in declaring the price of their toys, because in their world, what you buy is less about the object than the cash you threw at it. The uselessness of art makes any spending on it especially potent: buying a yacht is a tiny bit like buying a rowboat, and so retains a taint of practicality, but buying a great Picasso is like no other spending. Olav Velthuis, a Dutch sociologist who wrote Talking Prices, the best study of what art spending means, compares the top of the art market to the potlatches performed by the American Indians of the Pacific Northwest, where the goal was to ostentatiously give away, even destroy, as much of your wealth as possible—to show that you could. In the art-market equivalent, he says, prices keep mounting as collectors compete for this ‘super-status effect.'”

•••••••••

Carson Daly visits Mr. Brainwash’s Warholian vomitorium: