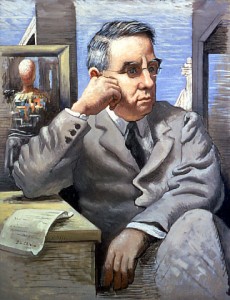

Dr. Albert C. Barnes was a working-class boy who made his money by inventing an antiseptic drug that is placed on the eyes of newborn babies.

Lacking all interest in false equivalency, Don Argott’s absorbing documentary takes sides in the battle for the legacy of an astounding art collection, points fingers, names names and seemingly gets it all right. The trove in question is $25 billion dollars of Post-Impressionistic art known as the Barnes Collection, which fell into the greedy hands of a dizzying array of politicians, power brokers and self-promoters after the deaths of collector Dr. Albert C. Barnes and the curator who succeeded him.

Barnes made his fortune in pharmaceuticals and decided to invest a good portion of the proceeds in art, after spending a couple of years educating himself on the topic. He had amazing taste, not only choosing Renoirs and Picassos but the best of them. Barnes built his treasures a gorgeous home in a suburban Philadelphia township and meticulously arranged the works so that they commented on each other. He decided to make the foundation largely an educational institution that was only open to the public a couple days a week. Matisse called the building “the only sane place to see art in America.”

From his perch in Lower Merion Township, Barnes carried on a war of words with the Philadelphia art, media and business elite, who had panned his collection after an early showing. He relished referring to the City of Brotherly love as an “‘intellectual slum.” He especially enjoyed jousting with Walter Annenberg, the right-wing publisher of the Philadelphia Inquirer who long sought to wrest the collection from his nemesis. When he died in a car accident in 1951, Barnes left an iron-clad will stating he never wanted his collection sold, broken up, moved, taken on tour or, god forbid, relocated to Philadelphia. His successor in running the foundation followed his wishes even as she allowed the building to pass into gentle disrepair. But eventually the foundation’s finances needed work, and the collection became a pawn for people who had their own agendas, especially those who desired to break Barnes’ will and move the art to Philadelphia rather than merely raising some money to preserve the collection as it was, which probably wouldn’t have been difficult to do.

What followed was similar to the legal shenanigans that went on after Mark Rothko’s death, except much more was at stake in this case, so everyone got lawyered up and brazenly attempted to get a piece of the legacy. Here’s a thorny thing: Because of all of this underhanded, illicit behavior, more people will get to see this incredible collection in its new location, even if it is going to be shown in a blockbuster fashion rather than the intimate way Barnes intended. But no amount of eyeballs getting to see this Matisse or that Van Gogh can make up for what went on. Figuratively if not necessarily literally, it was a crime.

Recent Film Posts:

- Classic DVD: The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

- Classic DVD: Fast, Cheap & Out of Control (1997)

- Classic DVD: Umberto D. (1952)

- Classic DVD: The Wicker Man (1973)

- Classic DVD: Blow-Up (1966)

- Classic DVD: Invasion of the Bodysnatchers (1978)

- Classic DVD: The Stepford Wives (1975)

- Classic DVD: Rollerball (1975)

- New DVD: Exit Through the Gift Shop

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Stay Hungry (1976)

- Classic DVD: Westworld (1973)

- Classic DVD: Slacker (1991)

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Decasia: The State of Decay (2002)

- Classic DVD: 32 Short Films About Glenn Gould (1993)

Tags: Dr. Albert C. Barnes

Subscribe to my free Substack newsletter, "Books I Read This Month." It's published on the final day of each month. Some new titles, some older, some rare.

Categories

About

Afflictor.com is the website of Darren D’Addario. Except where otherwise noted, all writing is his copyrighted material. ©2009-18.